It seems these days there are a lot of people who are passionate about a lot of things. They are passionate about their hobbies, passionate about their work, passionate about some cause, and of course there are those Passionate Kisses Mary Chapin Carpenter sings about.

For all I know there are people who are passionate about being passionate.

One thing most of my friends and acquaintances are decidedly not passionate about is politics. Oh, people are passionate about a potential candidate here and there. Once in a while someone will be passionate about an issue or, more likely, the country itself. I get that.

To clarify this, almost everyone cares about these things, but far fewer are passionate about them.

Sadly, as I look around, I see very little passion in practice. I hear the word a lot. I see it only a little. Here’s why.

Words mean things

Passion is a relatively new word. Not new like “meme,” a word coined by Richard Dawkins in the 1970s from the Greek mimema, which means “that which is imitated.” In that sense, meme is an element or unit of culture passed from one person to another by imitation.

I know that’s what it is because I saw it on Jeopardy!. They gave the definition, and not a single contestant knew it.

Had they given the definition Being willing to suffer for what you love, I wonder if any of them would have known to answer, “What is passion?” Because that is what it means.

We don’t use it much that way, as you’ve probably noticed. We’ve dumbed it down, as we have far too many words, to our profound loss.

In today’s common usage the suffering part is almost always missing, and yet it is the most important part. It is the differentiator. Check any modern thesaurus for passion and you’ll find words like enthusiasm, eagerness, emotion, excitement, and energy. All of those miss the mark.

First coined in the 12th century through the French from Latin, the root is passio, which means “suffering.” That comes from the Latin pati, which means “to suffer.” It was applied primarily to the sufferings of Christ that took place beginning with the Last Supper and ending with his death on the cross.

That is why Mel Gibson’s movie is called The Passion of the Christ, and why plays in Europe about the end of the life of Jesus on earth are called “passion plays.”

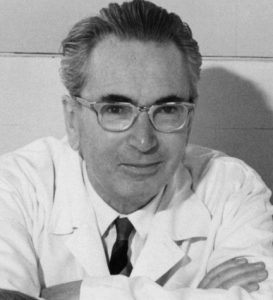

Viktor Frankl

As COVID rocked the world, we heard quite a bit about pathologists. Those are scientists who study the causes and effects of diseases. Have you ever wondered where that “pathologist” word came from?

It came from that same root I mentioned above, pati, which means “to suffer.” Many pathologists work in laboratory settings looking at tissue for diagnostic purposes, discovering the things that people suffer from.

And so we begin to understand the real idea behind passion.

Tell me you are passionate about something, and I may ask you this: What are you willing to suffer for it?

One man who knew he was willing to suffer was Viktor Frankl. You may know the name — and something about the man — from his deservedly famous and important book, Man’s Search For Meaning.

One man who knew he was willing to suffer was Viktor Frankl. You may know the name — and something about the man — from his deservedly famous and important book, Man’s Search For Meaning.

Published in 1946, the book tells of his experiences as a prisoner in several Nazi concentration camps during WW II. From my perspective it is outstanding and, frankly, a “must read” for anyone serious about going through the challenges of life.

But it was just recently that I discovered something about how Dr. Frankl became a prisoner. Author and speaker Kevin Hall shared it in his book Aspire, which I recently found in a used book sale.

He writes of a story Elly Frankl, Viktor’s second wife, told him and several other people:

…Viktor had arrived home from the American consulate with his travel visa in hand to find a large block of marble sitting on the table. His father had rescued it from a local synagogue that had been destroyed by the Nazis. [On this piece of marble was written]: “Honor thy Father and thy Mother, that thy days may be long upon the land.”

Viktor put his travel visa in his drawer and never used it. He willingly chose to stay and suffer alongside his parents.

Passion

And they were sent to concentration camps. Dr. Frankl was actually able to be with his father, who died in his arms.

Frankl’s own suffering would go on for several years, but it was a willing suffering. Part of that clearly was his Jewish faith as he chose to keep the commandment to honor his father and mother.

His wife died in the Bergen Belsen camp. His father died in the Theresienstadt Ghetto concentration camp. Walter, his brother, and their mother Elsa both died at Auschwitz. Viktor’s sister escaped to Austria, as he might have escaped to America.

I am certain those who escaped also suffered, but clearly in different ways. I might well have been among them had I been in the same circumstances as Viktor. But for the work he accomplished after his terrible ordeal, I am one among millions who is glad he made the choice he made.

There was no possible way, of course, for him to know ahead of time exactly how or how much he would suffer. That is true for us as well when we find that we care deeply about someone or something.

That could be others like your spouse or your children or your Christ. Or it might be a challenge, like your company or becoming an American Ninja Warrior. It could be selfish like power or riches or fame.

But you will not have true passion until you know you are willing to suffer for something, and the depth of your passion will be found in the depth of your willingness to suffer.

May your passion be great, and in it may you always…

Do good. It’s in you.

4 Responses

Excellent!

An education on what it means to be passionate about something.

To my dismay, I don’t think I am a very passionate guy.

Something to consider.

Understanding the term certainly makes a lot of our “passion” a little weaker, doesn’t it?

At the same time, though, it gives the passion we do have great strength, and that is very good indeed!

I read the book, Man’s Search for Meaning by Victor Frankl many years ago… I think it might be time to reread it.. thanks for a great post…

I actually read it again every couple of years, so I’m with you. And with this additional information that Frankl could have avoided it all, I’m sure my next reading will be even more informative and certainly more touching.

Thanks, Jim!