A few days ago I had the privilege of giving a talk to some student athletes at Grand Canyon University, and I had an assigned topic: Living an Uncommon Life.

Why, I wondered, would someone give that topic to me? Have I lived an uncommon life? Am I uncommon?

The answer to both questions is yes, although I was basically unaware of that until just a few years ago. At the discovery there had not been a blinding light (see Saul on the road to Damascus), and there had not been a “Eureka!” moment (see Archimedes leaping out of a tub).

The answer to both questions is yes, although I was basically unaware of that until just a few years ago. At the discovery there had not been a blinding light (see Saul on the road to Damascus), and there had not been a “Eureka!” moment (see Archimedes leaping out of a tub).

There had, however, been a steady growth in my thinking, and one day it hit me that I was living my life in an uncommon way.

I had no negative judgment about that, even though “uncommon” can be a synonym for “abnormal,” and all of us like being thought of as normal.

And I had no positive judgment, even knowing that “uncommon” as an adjective for life could mean “remarkable.” Even if we don’t attain remarkable but reach “unusual,” that could also be good.

This idea of not rushing to judgment is in itself uncommon, at least for most of us most of the time. Personally I am often quick to criticize myself. But eventually I decided that my life has been, and is, uncommon in a good way.

And so I thought about how I might advise college students — and you, because it is never too late — to go about living an uncommon life.

Carver’s George

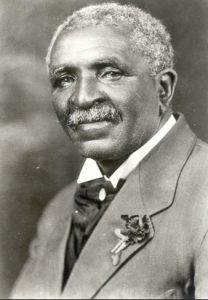

According to biographies, it took George Washington Carver quite a while to get his full name.

Born into slavery around 1864, George was the son of Giles and Mary. They were enslaved to Moses Carver, and so, automatically, were their children. A week after George’s birth he and his sister and their mother were kidnapped in Missouri and sold in Kentucky. Only George was rescued by agents of Moses Carver.

When slavery was abolished, Moses Carver and his wife Susan raised George and his brother James as their own. Susan taught George to read, and they encouraged him to learn.

When slavery was abolished, Moses Carver and his wife Susan raised George and his brother James as their own. Susan taught George to read, and they encouraged him to learn.

At a young age he traveled 10 miles by himself to try to get into a school. In that quest he met a woman (Mariah Watkins) from whom he wanted to rent a room. She asked his name and he said, “Carver’s George.” She told him that from now on he wouldn’t be Carver’s George, he would be George Carver. And so he was.

Later, to differentiate himself from another George Carver, he added a middle initial, choosing W. One day he was asked if the W stood for Washington, and he said something like, “Why not?”

Finally, he was George Washington Carver, one of the greatest names in American history.

Uncommon

In preparing for my talk, I found the following quote by Mr. Carver.

When you can do the common things of life in an uncommon way, you will command the attention of the world.

That became the basis for what I had to say, because it applied to all three bits of advice I wanted to share.

The second of those three was this: See people as people, not as one of their characteristics.

I told them the story of a friend I met in Silicon Valley. She was very creative, very smart, and she was also dealing with a neurological disorder. In addition to all of that, she was a lesbian.

We got along well, and even though I’ve lost touch with her I still consider her a friend.

One day as we worked together she asked me a challenging question.

“You know that I’m a lesbian, and I know that you are a Christian. Why haven’t you told me that I’m wrong?”

To be clear, she not only knew I was a Christian, she knew I did not believe her lifestyle was in agreement with what scripture teaches. But she also knew that I saw her not as a lesbian or a scientist or a writer or a woman but as a person, so we could discuss serious topics without fear. And, to our mutual benefit, we did.

Who am I?

One of the great songs in the musical Les Miserables is (in English) Who Am I? The song paints a moral dilemma for Jean Valjean, the hero of the story. He had been Prisoner 24601, but had escaped and made a good life for himself and others.

A policeman named Javert mistakes another man for Valjean and arrests him. Valjean witnesses the incident and has a chance to be free if he lets the innocent man take his place. He realizes the conundrum, “If I speak I am condemned. If I stay silent I am damned.” He turns himself in.

A policeman named Javert mistakes another man for Valjean and arrests him. Valjean witnesses the incident and has a chance to be free if he lets the innocent man take his place. He realizes the conundrum, “If I speak I am condemned. If I stay silent I am damned.” He turns himself in.

Javert was, at that point, an ideologue who could not see Jean Valjean as a person, only as 24601 — a number, not a name.

To live an uncommon life, know that you are a whole person and not some single trait. Know that you have a name and not a number. Do not let others identify you by one of your attributes, and do not identify them by one of theirs.

Ideologues are big on single characteristic identities. “He’s a Christian, so he is an LGBTQ+ hater.” “She’s a progressive, so you can’t trust anything she says.” “White? That makes him racist.”

And you?

If you want to live an uncommon life, do these two things: First, see others as people, not as some “thing.” This is hard, but we get a lot of chances to practice. Second, see yourself as a person. Making your identity a name and not a number will unlock the invisible shackles of the Javert’s of the world and make you free.

Seeing people as people is uncommon, and a great way to do good.

2 Responses

Often in Corporate America or America in general, we are like mice in the maze, using those prisoner’s numbers to navigate: he is a manager, she is in that division, etc. This is all right until one day the maze is in the mice.

We are all children of God and He loves each of us very much. That’s who I am.