We are just a few days from the 20th anniversary of what we collectively call “9/11.” If you are now at least 30 years old, I expect you know where you were on Tuesday, September 11, 2001, what you were doing, and what you did instead.

I was in the Red Carpet Club at San Francisco International Airport waiting for a flight to Chicago. I had run into a fellow I happened to know who owned a golf club company. He was going to San Diego, leaving earlier than I was, but we chatted for a while. I remember much of the conversation, though without the events of the day I would not.

He headed to his gate as I grabbed a cup of coffee and noticed several people standing around a small television set that hung on the wall. “What’s going on,” I asked no one and everyone.

“A plane has crashed into the World Trade Center. It was a commercial flight. It might have been an accident.” It was a little before 6 a.m. in San Francisco.

I pulled out my cell phone and called my wife. She had dropped me off at the airport and was in her office at the United Airlines maintenance base. One of my first thoughts was that this accident, although it was an American Airlines plane, was going to have a big impact on her job and her company.

While we were talking, the second plane hit the South Tower. Then we knew America was under attack.

9/11 — from the fairways to the rubble

Just 47 miles from the World Trade Centers, Ken Eichele (i – kull) was playing golf. That wasn’t his day job, it was his hobby and his passion. He had been playing since he was about six, the first golfer in his family. Now he was 50, and a good enough amateur to play in national tournaments. He took 9/11 off to play in the qualifier for the USGA Mid Amateur.

Just 47 miles from the World Trade Centers, Ken Eichele (i – kull) was playing golf. That wasn’t his day job, it was his hobby and his passion. He had been playing since he was about six, the first golfer in his family. Now he was 50, and a good enough amateur to play in national tournaments. He took 9/11 off to play in the qualifier for the USGA Mid Amateur.

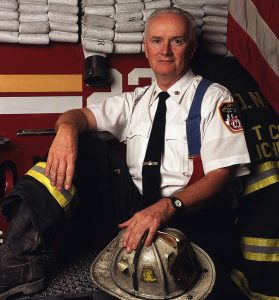

He was even par through 14 holes when he heard about the first crash. When he finished his round and saw what was happening, he knew he had to get back to his day job. He was a New York City fireman. In fact, he was a Battalion Chief, and he was in charge of several fire houses in the heart of Manhattan.

Ken eventually got back to his station, knowing that many of his people had already died and that more would. He and his colleagues spent the next 72 hours digging through the rubble, searching for survivors. They found only one.

In an interview with PGA Tour Radio, Ken said that one of the biggest miracles that day — and for the next few days — is that “no one got killed in the rescue and recovery effort.” He said every time we dug a tunnel “I would go in first. Not because I was the bravest, but because I wanted to die if those guys died.”

Nine firefighters from Ken’s engine company died that day. He estimates that he knew at least 100 others who died on or as a result of 9/11.

This is for the families

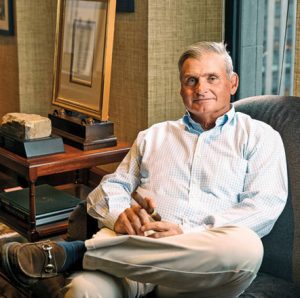

I’m not saying that all golfers are naturally good, though the game does teach honor. But playing in that same USGA Mid Amateur qualifier on 9/11 was Jimmy Dunne. He wasn’t a firefighter, he was an investment banker. Wealthy, an excellent golfer, and in line to take over as the head of Sandler O’Neill & Partners should Herman Sandler decide to retire. Jimmy’s best friend “Quack” was the other partner.

I’m not saying that all golfers are naturally good, though the game does teach honor. But playing in that same USGA Mid Amateur qualifier on 9/11 was Jimmy Dunne. He wasn’t a firefighter, he was an investment banker. Wealthy, an excellent golfer, and in line to take over as the head of Sandler O’Neill & Partners should Herman Sandler decide to retire. Jimmy’s best friend “Quack” was the other partner.

Herman, Quack, and 64 other employees at Sandler O’Neill, died on 9/11. Their offices were on the 104th floor of the South Tower. One of their employees, 24 year-old Welles Crowther, saved at least 12 others and died trying to save more.

Jimmy Dunne took the train back to New York from Bedford, and said he was the only one on the car. He remembered advice from his father: There are times to stand up. Also, he was determined that the negative effect hoped for by the terrorists would actually become a positive effect.

He met with the company’s CFO and asked her how long they could afford to pay salaries and benefits to all of their families that had lost someone. She thought maybe five years. So they did it, and still do.

The 66 Sandler O’Neill employees who died left behind 76 children. Dunne and a few others decided to start a foundation to fully fund the education, through college, of every one of those children. The last one, born six weeks after 9/11, is in college now.

Dunne has said that the good he did in announcing that salaries and benefits would continue for those whose lives were lost had an unexpected impact. It wasn’t the money, it was the good. The already successful firm actually became even more successful.

Becoming a hero

How do people like Jimmy Dunne, Welles Crowther, Ken Eichele, and literally hundreds of others do so much good in the midst of so much pain and suffering?

They do it the same way Eichele and Dunne learned to be extraordinarily good at their jobs and at golf. They worked at it, and they practiced.

If we looked back in the lives of any of the heroes of 9/11, we would find the same thing.

When I was a young man I shoveled a lot of snow for people who couldn’t shovel their own. I filled a lot of sandbags for places not mine that needed protection. Perhaps you did the same kinds of things, or perhaps you do things like that now.

All of those good deeds prepare your heart and mind for a day like 9/11.

There were many people that day who thought only of survival, and that is not wrong. But there were those who thought of others and did an incredible amount of good.

We call those people heroes, and they are. Their heroism might have become obvious on 9/11, but it was already there before.

Do good. It’s in you.

2 Responses

Remember that day well.

Nice write, as usual.

keep it going.

Thanks, Mark! It was a day that changed much, and in some ways made us better. But only because of the good that was done.