Vocabulary is one part of our knowledge that continues to grow as we go through life. That makes sense, because vocabulary itself is a word that means “all the words known and used by a particular person.” (Cambridge English Dictionary)

One way new words find their way into our vocabulary is through our work. I remember sitting in a meeting early in my time at a software company. I was the only one in the room who was not an engineer, and within minutes I had no idea what was being discussed.

Then someone said “mac address,” and I felt a glimmer of hope. I knew exactly what a Mac (as in Macintosh) was, even though I wasn’t sure about the “address” part of the phrase.

Fortunately I didn’t pop up and say, “I have a Mac!” because they were discussing Media Access Control. Huh?

But after almost six years at that company I could speak geek like nobody’s business, and sometimes I even knew what I was talking about.

The blue room

The blue room

That’s not just true in high-tech. My wife worked in the airline industry. You’ve probably been on one of her airplanes, or one of the competitor’s planes. Still, do you know what “the blue room” is? How about “dead heading?” The second doesn’t mean you’re on your way to a Grateful Dead concert, it means you’re going to work. The “blue” doesn’t refer to the room’s paint color but to the color of the chemical used in flushing the toilet in it.

See how your vocabulary has grown already?

Every industry and almost every activity has it’s own jargon. (Hey, another word!) A birdie in golf is good, an eagle is better, and an albatross is even better. Sub-par is great in golf, not good when you’re telling the doctor how you feel.

There are also words we learn because they are repeated so frequently and widely in a short period of time that they find their way into our vocabulary almost without us realizing it.

12 Letters

The word we’ve all learned, even if we haven’t used it much, is asymptomatic. (Say that fast six times in a row.) At 12 letters, it’s a longer word than most that we know. It literally means you “have or present no symptoms of an illness.” If you don’t have an illness, guess what else you don’t have. Symptoms.

However you can have an illness and still not have symptoms. Lots of cancers are like that, including one I had. So it’s fairly common to do cancer screenings of people who don’t have any symptoms but might be at risk.

When it comes to COVID-19 the same thing is true. No symptoms might mean no illness, but not necessarily. It is possible to be infected and still be asymptomatic. The problem here, of course, is that COVID-19 is transmissible. (Another new word!) Unlike cancer, you can spread COVID-19 to someone else. You might even be able to do that if you have it and are asymptomatic.

Masks

So we stay six feet apart, we wash our hands, we don’t touch our face, and we wear a mask when we’re out in public, but mostly we don’t go out in public. We definitely do not go into crowds. (Remember crowds?) All of that is intended to keep us from spreading a disease we may have to someone else, and to keep that someone else from spreading a disease they may have to us.

A lot of people have wondered at the benefit of all that, especially when considering the psychological impact. We were created to be in community with each other, after all, and isolation is known to be harmful. In fact the worst form of punishment we can inflict on someone (other than death) is solitary confinement.

That doesn’t even count the economic impact, because many businesses depend on a number of people being in close proximity to one another. Think football stadiums, restaurants, retail stores, hair salons and movie theaters.

Asymptomatic do gooders

Once we have a new word, we like to apply it to areas for which it was not originally intended. After all, we have a new word! Nothing wrong with that, so I’m going to do it.

What I want to know is this: is it possible to be an asymptomatic do gooder?

In other words, is it possible that inside you resides the condition of doing good, but nobody can see it? There are no symptoms, nothing that even a close observer would notice, indicating that you are likely to do good.

To answer that question, I suppose we should look at the symptoms of someone we know who has the condition.

A do gooder with pointy hair

A do gooder with pointy hair

In another post I’ll write more about Guy Fieri, he of Triple D fame. The man has the “do good” condition, and the symptoms are obvious. Have you ever seen him do an interview where he made himself the star? Nope.

How about an interview at a diner, drive in or dive where you didn’t say, “I’d like to give that place a try?”

Have you seen what he’s been doing during the pandemic? He started a fund to help out-of-work restaurant employees. The idea was that they could apply for a $500 grant from the relief fund. To date they’ve paid out 40,000 of those grants! That was the absolute max they planned on, but are they going to stop there? I doubt it.

Using that as a kind of standard, how often have I had a conversation and made myself the star? When I do that it’s not because I’m bad, I’m just asymptomatic.

How often have I said, “There’s a group of people who could use some help” and then done nothing about it? There is good in me, I promise. But I’m asymptomatic.

When have I failed to lift up someone else to the public, or even to just another person, when I was in the position to do so? That wasn’t me being thoughtless, I was only asymptomatic.

Let it show

Personally I think it would be great if we always had symptoms that revealed the things that lived in us, both good and bad. In the case of the bad things, like an illness, we could then treat it earlier. In the case of a good thing, like compassion, we could begin to develop it earlier.

But many of the things that live in us don’t show. Or if they do show, we don’t recognize what we are seeing as symptoms of something deeper.

On the bad side of that, I’ve known people who have said, “It’s just a cold” when in fact it was pneumonia. Put enough of a scare in people, though, and the tiniest possible symptom makes us delve into the possibilities. We saw that a lot during the COVID-19 pandemic. People coughed or felt a little feverish and ran to the doctor, demanding to know if they had the illness.

That is understandable, because earlier detection is always best. So how do we detect what’s in us?

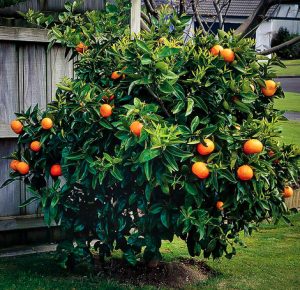

Fruit inspectors

Fruit inspectors

In the Bible there are a couple of lists in close proximity to each other. One lists the characteristics of people who live their lives by the spirit of God. It calls itself “the fruit of the spirit.” It includes love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

When you see those symptoms (that “fruit”) then you know what kind of person you are dealing with. But there is a bad list, too, and it’s even longer: “sexual immorality, impurity, sensuality, idolatry, sorcery, enmity, strife, jealousy, fits of anger, rivalries, dissensions, divisions, envy, drunkenness, orgies, and things like these.”

The first list is “the fruit of the spirit” while the second list is “the works of the flesh.” We might call it “the fruit of the flesh,” and if we did, then we’d just have to be fruit inspectors.

The great thing is, we don’t just have to inspect someone else (or everyone else), but we definitely need to inspect the fruit of our own lives.

Practice

You may see (and this is weird in nature), both the fruit of the spirit and the fruit of the flesh when you inspect your own life. The goal is to get to the point where that “fruit of the flesh” fruit is totally eradicated and the fruit of the spirit is growing like crazy!

How do you do that? A lot of it is a matter of choice and a lot of it is a matter of practice. It’s like the old joke about a fellow who finally made it to New York City. He really wanted to go to Carnegie Hall, but he got lost on the way. Undeterred, he stopped a fellow on the street who was carrying a violin case.

“How do I get to Carnegie Hall,” he asked the musician, who looked at him with sad eyes and said, “Practice, young man. Practice.” And walked away.

Practice love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Do all that every day and let people see it. Whether or not you make it to Carnegie Hall, this is no time to be asymptomatic.

Are You Asymptomatic?

Vocabulary is one part of our knowledge that continues to grow as we go through life. That makes sense, because vocabulary itself is a word that means “all the words known and used by a particular person.” (Cambridge English Dictionary)

One way new words find their way into our vocabulary is through our work. I remember sitting in a meeting early in my time at a software company. I was the only one in the room who was not an engineer, and within minutes I had no idea what was being discussed.

Then someone said “mac address,” and I felt a glimmer of hope. I knew exactly what a Mac (as in Macintosh) was, even though I wasn’t sure about the “address” part of the phrase.

Fortunately I didn’t pop up and say, “I have a Mac!” because they were discussing Media Access Control. Huh?

But after almost six years at that company I could speak geek like nobody’s business, and sometimes I even knew what I was talking about.

That’s not just true in high-tech. My wife worked in the airline industry. You’ve probably been on one of her airplanes, or one of the competitor’s planes. Still, do you know what “the blue room” is? How about “dead heading?” The second doesn’t mean you’re on your way to a Grateful Dead concert, it means you’re going to work. The “blue” doesn’t refer to the room’s paint color but to the color of the chemical used in flushing the toilet in it.

See how your vocabulary has grown already?

Every industry and almost every activity has it’s own jargon. (Hey, another word!) A birdie in golf is good, an eagle is better, and an albatross is even better. Sub-par is great in golf, not good when you’re telling the doctor how you feel.

There are also words we learn because they are repeated so frequently and widely in a short period of time that they find their way into our vocabulary almost without us realizing it.

12 Letters

The word we’ve all learned, even if we haven’t used it much, is asymptomatic. (Say that fast six times in a row.) At 12 letters, it’s a longer word than most that we know. It literally means you “have or present no symptoms of an illness.” If you don’t have an illness, guess what else you don’t have. Symptoms.

However you can have an illness and still not have symptoms. Lots of cancers are like that, including one I had. So it’s fairly common to do cancer screenings of people who don’t have any symptoms but might be at risk.

When it comes to COVID-19 the same thing is true. No symptoms might mean no illness, but not necessarily. It is possible to be infected and still be asymptomatic. The problem here, of course, is that COVID-19 is transmissible. (Another new word!) Unlike cancer, you can spread COVID-19 to someone else. You might even be able to do that if you have it and are asymptomatic.

Masks

So we stay six feet apart, we wash our hands, we don’t touch our face, and we wear a mask when we’re out in public, but mostly we don’t go out in public. We definitely do not go into crowds. (Remember crowds?) All of that is intended to keep us from spreading a disease we may have to someone else, and to keep that someone else from spreading a disease they may have to us.

A lot of people have wondered at the benefit of all that, especially when considering the psychological impact. We were created to be in community with each other, after all, and isolation is known to be harmful. In fact the worst form of punishment we can inflict on someone (other than death) is solitary confinement.

That doesn’t even count the economic impact, because many businesses depend on a number of people being in close proximity to one another. Think football stadiums, restaurants, retail stores, hair salons and movie theaters.

Asymptomatic do gooders

Once we have a new word, we like to apply it to areas for which it was not originally intended. After all, we have a new word! Nothing wrong with that, so I’m going to do it.

What I want to know is this: is it possible to be an asymptomatic do gooder?

In other words, is it possible that inside you resides the condition of doing good, but nobody can see it? There are no symptoms, nothing that even a close observer would notice, indicating that you are likely to do good.

To answer that question, I suppose we should look at the symptoms of someone we know who has the condition.

In another post I’ll write more about Guy Fieri, he of Triple D fame. The man has the “do good” condition, and the symptoms are obvious. Have you ever seen him do an interview where he made himself the star? Nope.

How about an interview at a diner, drive in or dive where you didn’t say, “I’d like to give that place a try?”

Have you seen what he’s been doing during the pandemic? He started a fund to help out-of-work restaurant employees. The idea was that they could apply for a $500 grant from the relief fund. To date they’ve paid out 40,000 of those grants! That was the absolute max they planned on, but are they going to stop there? I doubt it.

Using that as a kind of standard, how often have I had a conversation and made myself the star? When I do that it’s not because I’m bad, I’m just asymptomatic.

How often have I said, “There’s a group of people who could use some help” and then done nothing about it? There is good in me, I promise. But I’m asymptomatic.

When have I failed to lift up someone else to the public, or even to just another person, when I was in the position to do so? That wasn’t me being thoughtless, I was only asymptomatic.

Let it show

Personally I think it would be great if we always had symptoms that revealed the things that lived in us, both good and bad. In the case of the bad things, like an illness, we could then treat it earlier. In the case of a good thing, like compassion, we could begin to develop it earlier.

But many of the things that live in us don’t show. Or if they do show, we don’t recognize what we are seeing as symptoms of something deeper.

On the bad side of that, I’ve known people who have said, “It’s just a cold” when in fact it was pneumonia. Put enough of a scare in people, though, and the tiniest possible symptom makes us delve into the possibilities. We saw that a lot during the COVID-19 pandemic. People coughed or felt a little feverish and ran to the doctor, demanding to know if they had the illness.

That is understandable, because earlier detection is always best. So how do we detect what’s in us?

In the Bible there are a couple of lists in close proximity to each other. One lists the characteristics of people who live their lives by the spirit of God. It calls itself “the fruit of the spirit.” It includes love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control.

When you see those symptoms (that “fruit”) then you know what kind of person you are dealing with. But there is a bad list, too, and it’s even longer: “sexual immorality, impurity, sensuality, idolatry, sorcery, enmity, strife, jealousy, fits of anger, rivalries, dissensions, divisions, envy, drunkenness, orgies, and things like these.”

The first list is “the fruit of the spirit” while the second list is “the works of the flesh.” We might call it “the fruit of the flesh,” and if we did, then we’d just have to be fruit inspectors.

The great thing is, we don’t just have to inspect someone else (or everyone else), but we definitely need to inspect the fruit of our own lives.

Practice

You may see (and this is weird in nature), both the fruit of the spirit and the fruit of the flesh when you inspect your own life. The goal is to get to the point where that “fruit of the flesh” fruit is totally eradicated and the fruit of the spirit is growing like crazy!

How do you do that? A lot of it is a matter of choice and a lot of it is a matter of practice. It’s like the old joke about a fellow who finally made it to New York City. He really wanted to go to Carnegie Hall, but he got lost on the way. Undeterred, he stopped a fellow on the street who was carrying a violin case.

“How do I get to Carnegie Hall,” he asked the musician, who looked at him with sad eyes and said, “Practice, young man. Practice.” And walked away.

Practice love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Do all that every day and let people see it. Whether or not you make it to Carnegie Hall, this is no time to be asymptomatic.

Get The Do Good U news

We won’t send you spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Let's Do Some Good

Learn more about our programs.